By Jon Kelly BBC News Magazine, Washington DC

Two centuries after her most famous work, Jane Austen inspires

huge devotion in the US. What makes this most English of writers so appealing

to Americans?

She

wrote it herself in 1813: "How much sooner one tires of any thing than of

a book."

Jane

Austen's own work is a case in point. It may be 200 years since her most

celebrated novel, Pride and Prejudice, was published, but in the US she is the

subject of more wildly devotional fan-worship than ever.

With

their conventions, Regency costumes and self-written "sequels" to

their heroine's novels, Austen's most dedicated adherents display a fervency

easily rivalling that of the subcultures around Star Trek or Harry Potter.

Some

Janeites, as they call themselves, write their own fiction imagining the

marital exploits of Mr and Mrs Darcy. Others don elaborate period dress and

throw Jane Austen-themed tea parties and balls.

Blogs and forums dedicated to Austen and

Austen-style fan fiction abound across the internet. The Jane Austen

Society of North America (Jasna)

boasts 4,500 members and no fewer than 65 branches.

In

October 2012, over 700 Janeites - many attired in bonnets and early 19th

Century-style dresses - gathered in Brooklyn, New York for a Jasna event that

incorporated three days of lectures, dance workshops, antique exhibitions, a

banquet and a ball.

It's

a curious phenomenon when one considers that Austen won little fame in her own

lifetime, dying aged 41 in 1817 with only six novels to her name.

While

she may be regarded as one of the greatest writers in English literature, it's

difficult to imagine a similar level of fandom emerging around a novelist like,

say, Charles Dickens.

For

all that her stories can be by turns bleak and waspish, however, it's the

romance of Austen's world that many Janeites say drew them in.

"There's

a longing for the elegance of the time," says Myretta Robens, who manages

one of the most popular US Austen fan sites, The Republic of Pemberley. "It's an escape."

Screen

versions such as Andrew Davies's 1995 BBC adaptation Pride and Prejudice -

famously featuring Colin Firth in wet breeches as Mr Darcy - and the 2005 film

starring Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Bennet, contributed to an upswing of

interest in all things Austen.

But this alone does not explain why so many

Janeites want to inhabit their favourite writer's world, whether by dressing up

in the fashions of the era or writing their own Regency fiction.

"I

think it's to do with the fact that we only have six novels and she died fairly

young," says Laurel Ann Nattress, who runs the Austenprose blog and edited Jane Austen Made Me Do

It, a collection of short stories inspired by the author.

"People just love her characters and they

don't want to give them up."

Robens,

however, believes there is a more straightforward reason why readers feel

compelled to compose their own versions.

"Quite

frankly, I think a lot of people want more sex, particularly with Elizabeth and

Darcy," she says.

A

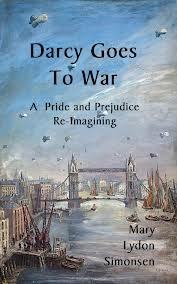

perusal of Austen fan sights reveals an abundance of stories with titles like

Darcy Meets His Match and The Education of Miss Bennet.

It

is not only online amateurs who have attempted to re-imagine these characters,

however. Linda Berdoll's 2004 Pride and Prejudice "sequel", Mr Darcy

Takes A Wife, was a bestseller.

Helen

Fielding has stated her own Bridget Jones's Diary was loosely based on the

original Austen plotline - hence the presence of a character named Darcy,

played in the film version by Firth. The 1995 comedy Clueless was inspired by

Austen's Emma.

Nor is all ersatz Austen concerned with

affairs of the heart. PD James's Death Comes to Pemberley involves the married

Darcys in a murder mystery. Seth Grahame-Smith's Pride and Prejudice and

Zombies re-casts the original novel in an alternate version of Regency England

populated by hordes of undead.

The

Janeite subculture was itself the subject of a popular comic novel, Shannon

Hale's Austenland, a movie version of which premiered at the 2013 Sundance film

festival.

Nonetheless,

it might be seen as incongruous that Austen's fandom is so extensive in the US,

a nation founded on the rejection of aristocracy and old world manners and

traditions.

Indeed,

when Pride and Prejudice was first published, the UK and US were at war.

Nattress, who lives in Snohomish, Washington state, believes US Janeism is an

expression of a persistent Anglophile streak in American society.

"I

think that we look back to the motherland in many respects," she says.

"Look

at the incredible impact Downton Abbey has had over here. It's a perfect

example of how America is fascinated by British culture."

But

while Austen's sharp prose, ironic wit and vivid characterisation are all key

to her appeal, Robens believes that it is the romantic entanglements of her

strong-willed heroines that draw so many to the books.

"It's

women, in general, who fall in love with them," says Robens. "It's a

truth universally acknowledged that women want to read about

relationships."

From

The Janeites by Rudyard Kipling

It

was not always the case that Austen's fanbase was seen in these terms, however.

Indeed,

the term Janeite was initially coined by the male literary critic George

Saintsbury. Rudyard Kipling's 1926 short story The Janeites describes a group

of soldiers brought together by their passion for the works of Austen.

According

to Claudia L Johnson, an Austen expert and professor of English literature at

Princeton University, the author was widely regarded well into the 20th Century

not as a romantic novelist but as a steely, tough-minded, sardonic social

critic.

"Now,

alas, Austen is typically seen (by my students and others) as chick lit and she

is beloved for her love stories," laments Johnson, author of Jane Austen:

Women, Politics, and the Novel. "I think this is a real loss."

Johnson draws a distinction between the

extravagant, amateur Janeites and their more academic counterparts, whom she

terms Austenites. They are not categorisations which meet with much approval

among most fans.

Nonetheless,

Johnson acknowledges that attempting to remake Austen in the reader's own image

is a valid exercise.

"Janeites

- at least in the US - regard their excesses with a curious mixture of irony

and seriousness," she says.

"They

know it's absurd to throw tea parties, but the fundamental drive here - to try

to be somehow connected with the world and life of a beloved author - isn't

absurd."

It's

likely Austen would agree. In her early writing she pastiched the 18th

Century's so-called novels of sensibility and parodied historical tomes.

As

the author herself put it in Pride and Prejudice: "A person who can write

a long letter, with ease, cannot write ill."